No animal is an island

On the joys of companionship.

Only a few species incline towards solitude. Most of the rest of us tend to become anxious when we find ourselves without a community to belong to.

This summer has been one of big changes here at the Academy, with several new additions to the faculty. This is now a two dog, two horse, three goat, three rabbit operation--not counting the cat, the turkey, and multiple generations of guinea fowl and chickens (of whom I have lost count).

Allow me to introduce some of these new members (the poultry will have to be covered in another post).

One cloud feels lonely (ancient rabbit proverb)

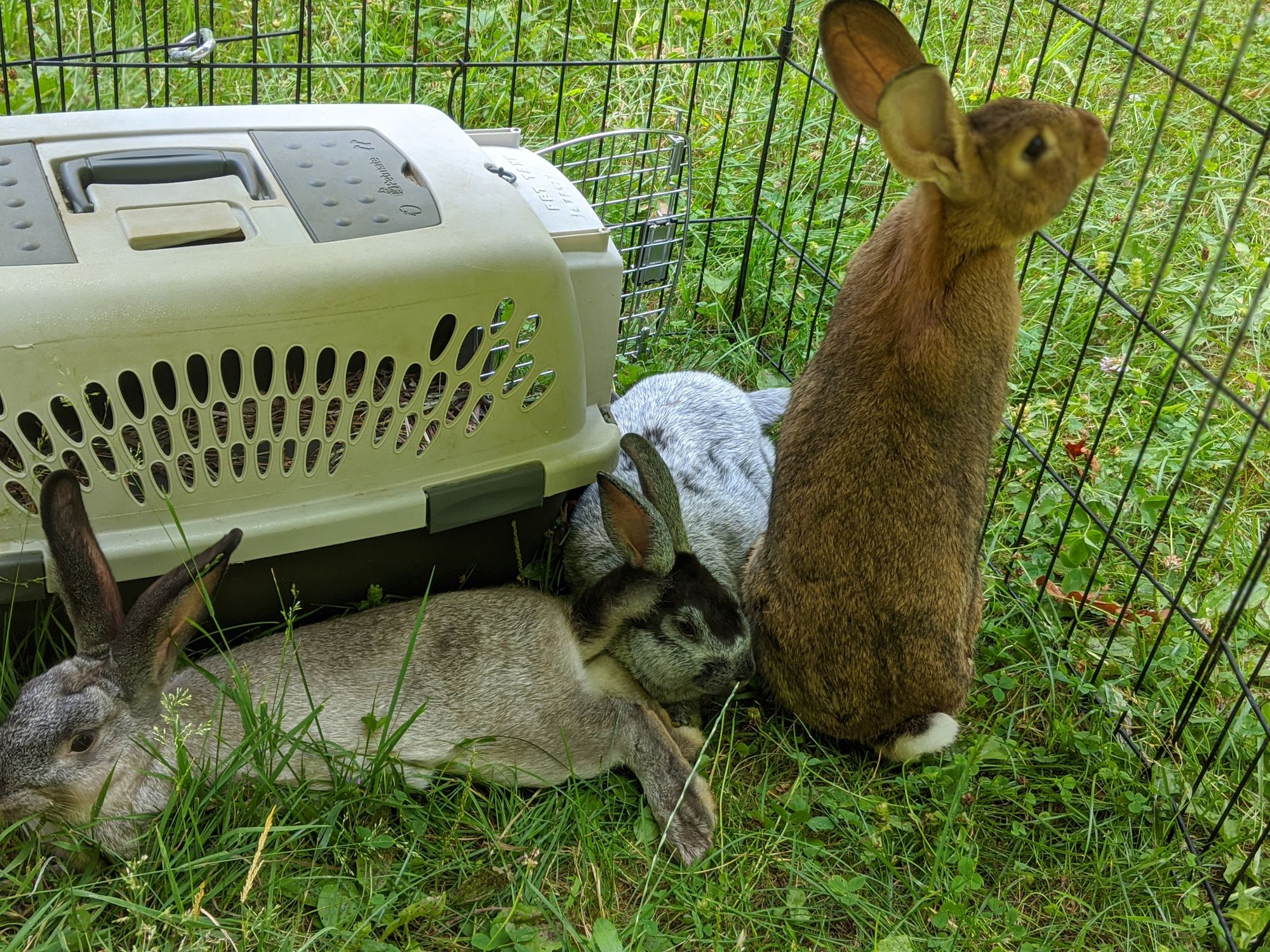

Not pictured in the faculty portrait above are the rabbits. Mostly for reasons of their own safety, they do not roam freely with all the other animals. Peter Kroptkin the Rabbit was the first of his kind to join us.

Most breeders fetishize purebreeds for their predictable expression of genetic traits, but I'm a big believer in hybrid vigor. A delightful blend of all the meat breeds favoured in North America (New Zealand, Californian, Flemish Giant, Rex, Champagne d'Argent), Peter is the first occupant of the position of Big Daddy in the Academy's rabbit colony to be. (Male rabbits can fight each other viciously, the victor even castrating the loser, so I'm trying to eliminate that problem by retaining only one breeding buck at a time.)

Peter spent his first week here moping around rather pathetically. It became obvious that it was imperative to get him some companions sooner rather than later. In early June I brought home Rosa Luxemburg, a Champagne d'Argent doe who is a couple weeks younger than him.

Peter was visibly overjoyed and these two became inseperable. As the weeks went by, Rosa's fur became more silver as she aged.

It seemed clear that if another doe was to be introduced it needed to happen while they were still all young enough to accept the newcomer (adult female rabbits are extremely territorial).

So in mid July, they were joined by Ida B. Wells (a Flemish Giant/Rex doe, 2 weeks older than the other two).

It seems rabbits are just as social as Watership Down lead me to believe.

While most domestic rabbits are kept in fairly small individual cages and pellet-fed, in the wild they live in large colonies centered on a warren, a network of interconnected burrows.

Against conventional wisdom, I've decided to keep this small group together. They aren't caged but currently grazed in a small enclosure on the lawn by day and housed in a box stall in the barn by night. I'm hoping to convert the dog run beside the garage into a permanent colony, but this will take quite a bit of work, since rabbits really like to dig.

Traditionally bucks and does are separated at 12 weeks, lest they breed before the does are physically ready to have a viable litter. I'm betting that this is less of a worry when the does are able to be physically active and not pumped full of high calorie feed to maximize their growth rate. Intense summer heat also tends to make male rabbits sterile. But we will see.

All the pretty horses

Like the rabbits in their warrens, horses naturally incline to life in a herd, with its strength in numbers and opportunities for social interaction. Federica was quite evidently unhappy as the only one of her kind.

While Federica came to form a herd bond with the three goats, she was often the only one on the lookout for threats. She is already highstrung in nature, and being the lone horse only made her more anxious.

As it happened, my friend Jen Derksen, had a wonderful sweet natured gelding she was looking to rehome. Logan didn't quite fit in with her herd, but we guessed that he and Federica might be a good match, so he came to live here at the end of May.

Logan is a 10 year old Thoroughbred draft cross. His dam is part Belgian, and that lends him his heft and his chill. Given how long he has lived with his name, he is renamed after Logan the Orator, the 18th-century Cayuga who was notably accepting of the white settlers until they murdered his family. Our Logan is also very easygoing until you really piss him off.

Logan's calm ways are welcome foil to Federica's more intense nature. Their relationship has evolved through every permutation in the past two months, and now seems to have settled into an older brother/younger sister vibe.

The heart of a dog

Finally, Harriet, who has been an only child since she came to us at 8 weeks old, now also has her own younger brother to play with and boss around.

Leon Trotsky, who will be a year old at the end of this week, is a livestock guardian dog, most likely a Great Pyrenees/Anatolian Shepherd mix. He came to us from a rescue, as he was not thriving in his previous situation.

Dogs of Leon's type are working dogs, who are instinctually driven to protect livestock. Unlike Harriet, Leon lives outside. It is all he has ever known. His double-coat acts much as a sheep's fleece to protect him from the elements. He is not yet neutered, as giant breeds continue growing until age two. The latter condition and his guardian dog ways leave him inclined to pee on everything.

Leon is much more people-focused than the typical LGD, and this may be part of why he did not fare well in his previous situation. He wants a lot of love from his people.

Leon is Harriet's opposite in temperament. Where she is super intense, bossy, and excels at abstract thinking, Leon is lowkey, eager to please, and more attuned to his surroundings (his emotional intelligence is notably superior to hers). His most endearing talent is the ability to nap if nothing interesting is happening.

The odd cat out

There is always an exception to the rule,and usually it's a cat. George, my ancient black cat--estimated age 17--is now the only remaining singleton at the Academy. Even Prez the turkey has bonded to his age cohort of chickens. But George is steadfastly solitary.

For 15 years he tolerated the company of Jeffrey, who died the first winter we were here. I thought George would miss Jeffrey when he was gone, but he almost seemed relieved.

George is no longer as spry (nor as portly) as he once was, but nowadays his only remaining occupations are sleeping, hunting rodents when he feels like it, loudly demanding his tithe of fresh goat milk when Elaine is on the milking stand, and going for leisurely evening strolls.

His solitary existence may be less of a counter-argument to the joys of companionship and more suggestive of the life-enhancing benefits of (a) self-determination, (b) unpasteurized small scale dairy, (c) staying active into one's golden years, (d) all of the above.

What I have learned

There are no pets here. Everyone has a job. But those jobs don't completely map onto the traditional labour of farm animals, such as providing food or fibre/fur or future generations.

Providing fertilizer, grounds maintenance work, pest control, security, beauty, and amusement also add value.

But the animals don't just offer companionship to each other. They are our co-workers and comrades here at the Academy.

Interspecies collegiality has been the most powerful revelation. The health benefits of companionship have been long underrated. But in the summer of Covid-19, it's never been clearer how important it is to live and work in the company of other beings.

Living in community with these animals is therapeutic in every sense of the word.